An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called Turning Adversity Into Felicity

There is happiness in watching one’s mind change from that which was tightly constricted, self-absorbed and contracted into that which is spacious, lifted, calm, receptive, generous, and has a strong degree of clarity! Watching oneself grow in that way, haven’t you ever noticed that there are so many things that bring us joy? Like I said, we can have love, we can have money, we can have good food, we can have a great car, there are so many things that make us happy for a little while. But my experience has been—and maybe this is the same for you as well—that nothing makes me feel more joy and more happiness than watching my own practice mature, watching my mind transform into something it wasn’t before, watching the mind grow into something which is relaxed, which has a kind of sophistication to it. A sophistication that’s based not on closing the eyes, but engaging in a purposeful way, to watch myself develop new habits, to watch myself grow through things that I could not grow through before and suddenly I have mastered.

These are the real joys in my life. These are the things that sustain me, and I think if you think about it, you’ll notice that every time you’ve gone through a period of spiritual development and growth, you will find that you have become much more satisfied with yourself than anything else could have made you. Happier. Oh, it may not be the jump-up-and-down kind of happy we get when we get that new car, but it’s a quiet, supportive, dignified, noble kind of happiness.

And what else brings us the motivation to practice that way, brings us the necessary components that unfortunately do what we need, gives us that old kick in the butt, other than adversity? It’s adversity that ultimately comes to be the greatest blessing in our lives. Not that you want it. You don’t go, “Hey! Bring on the adversity! Bring it on!” That’s not what you want to do. Of course, we’re not going to think like that. Nobody wants adversity, but the trick here–and the point of this teaching–is that we can transform adversity into extraordinary benefit through utilizing the gifts that were given to us by the Guru, through using all the objects of refuge as our ultimate support and our true refuge, through not relying on the unpredictable, temporary, mixed events of samsara and grasping at them as though they were our object of refuge, but instead relying on the Guru as the supreme object of refuge, and engaging in the Guru’s teachings, following in the Guru’s example, using that method that was given. If we do that and transform adversity into great benefit, the benefit is extraordinary.

It’s extraordinary. It has a depth to it that can’t be gotten any other way. That’s all I can say about it. If, let’s say, in Never-Never Land—we’re back to our Peter Pan thinking—it is possible to experience poverty, to wish upon a star and suddenly a million dollar check is in our hand, the superficiality of that kind of happiness would be evident from that point on through the rest of your life because all you have there is a million dollars, and a million dollars in a mind that is completely dissatisfied, untrained, unhappy, not relaxed, and does not make happiness. And the first people who will tell you that are people with a million dollars who are not happy.

But if, on the other hand, you experience impoverishment and begin to create through your practice, in a disciplined, compassionate and honest way, the causes for prosperity, the causes for riches of all kinds to enter into your life through the practice of generosity, through the practice of offering, through the practice of the discipline of engaging in Dharma practice, through all of the many means that have been prescribed by the teacher, then not only will the impoverishment cease, but there are layers and layers and dimensions and dimensions of supportive change that intertwine and are part of and are inseparable from the feeling of opulence and wealth. And they all become a part of you. You develop new habits that are a part of your awareness, a part of your perception, a part of the cause and effect relationships that are the karma of your experience of continuum. And these are the blessings that when you actually die and enter into the bardo remain with you, not the million dollar check. You can’t take that with you. But the practice that you have engaged in, that has created the cause for happiness and prosperity, the habit of that, the merit of that, the virtue of that, the karma of that, the causes, these seeds go with you into the bardo experience and ripen there. They go with you into your next incarnation and ripen there. This is the method.

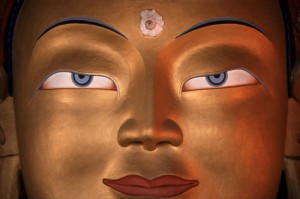

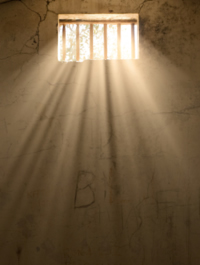

And I’ll tell you that if you, with faith and confidence and patience, engage in that kind of practice, not making up your own religion, not having bliss-ninny thinking or being forever Peter Pan, if with faith and confidence and fervent regard you actually engage in what the Guru has taught you, then it’s as though you have accomplished the most extraordinary spiritual practice. You are actually at that point a Dharma practitioner, an intelligent one, creating cause and effect relationships that are beneficial. When you have accomplished in that way and you have done so with the idea that with faith and fervent regard you are entering that door of liberation, out of that burning room and into happiness, then at that point it’s as though you have the very thumbprint of the guru on the fabric of your mind and on the fabric of your heart. You have become like one of the Buddha’s sons and daughters. You have become disciples of the Lamas who have accomplished, who have achieved all of the necessary components of enlightenment and have returned for the sake of sentient beings. You have accomplished what the Guru has come to the world to invest in you, and it’s the only way to do it.

Simply repeating phrases, simply blinding yourself to reality, simply warping your own mind and denying what you see, simply skating through life on the surface as though there were no cause and effect relationships, as though you were basically a complete idiot, this is not receiving the blessing of the Guru. This is not transforming adversity into felicity.

To open the eyes, to open the heart with confidence and patience, to accomplish the teachings that were actually given to us with courage, the courage of accepting responsibility, the responsibility of your own life, of your own reality, and holding that responsibility like a treasure, because once it is in your hand, it is yours. No one can take that away from you. Guru Rinpoche himself, if he was inclined to do so, could not take away from you the potency of how you can transform your life through practice. No one can take that away from you. It is the one thing that you have now in your hand that you will never be parted from unless you yourself give it up, and even then, although you’ve denied it, it’s still there. In that way you are practicing this teaching that is so often spoken of, “turning and transforming adversity into felicity”. Having practiced in that way, you come out of the experience of lack (or whatever it was that you had), deeper, more relaxed, more spacious, more sophisticated, more developed and happier.

You know in your heart when you have achieved that kind of success, when you have practiced in that way, and you also know when you’re faking. My advice to you, therefore, is to look within with honesty and clarity and practice what you have been taught, and in this way your life will be transformed into a vehicle of blessings. And it will always be that way. And it is the one wealth that you have that you can actually take with you.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo