The following is an excerpt from a teaching by His Holiness Penor Rinpoche offered during retreat at Palyul Ling in New York:

His Holiness Penor Rinpoche

Heart Teaching HT22

About Guru Yoga

In the beginning of the practice, try to watch your mind and thoughts. If you have any afflictive emotions or negative thoughts, try to abandon them. Then try to give rise to virtuous thoughts, such as devotion, faith and inclination; and in that way try to have the right intention.

Guru Yoga practice is something that we need to carry through until we attain enlightenment. Some think that we just need to do the Guru Yoga practice during Ngӧndro and the Four Foundations practice, but other than that, we don’t need it. We should not think that way. To attain complete enlightenment, Buddhahood, we have to completely depend upon the Guru’s instructions, and rely on the Guru. As we apply that instruction and teaching into practice, then we could have that fruition. That is why the Guru Yoga practice is important. So, without fabrication in one’s mind, abide in the great unelaborated empty nature, and carry through with the supplication prayers.

About Chӧd – Cutting through thoughts and afflictive emotions

In Ngӧndro, there actually is a Chӧd practice. Before we didn’t have enough conditions to really do it. In general, you do the practice with damarus and bells. Evening is a good time to do some of the Chӧd practices. At that hour the chant master and other lamas do the Chӧd practices. As you do the Chӧd, follow along and chant the tunes together. And when you use your big damarus and bells, follow together as a group in sync, instead of some doing it this way and some doing it that way, which sounds very strange. Doing it haphazardly like that is a joke. So always try to do the practice together with everything working together.

The Chӧd practice in the Namchö is only one page, so it is easy and good in that way. The Tibetan word, “Chӧd,” means cutting through all the afflictive emotions and thoughts, and then establishing the nature of emptiness. In the Chӧd visualization, as one chants with faith, everything is cut through in the nature of emptiness.

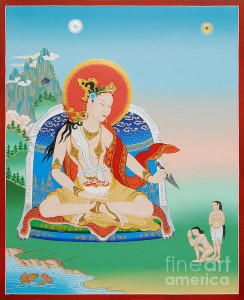

When you say the second Phet, your consciousness shoots out onto the ground as Vajravarahi (Dorje Phagmo), the size of a pea. When you say Phet again, then Vajravarahi becomes about the size of a finger. After that when you say Phet, then you visualize Vajravarahi about the size of a cubit. After that when you say Phet, Vajravarahi becomes huge, filling all space.

In her right hand, Vajravarahi holds a curved knife and in her left hand, she holds a skull cup. She has all the bone ornaments. Your consciousness is manifested or transformed into Vajravarahi, and your body is like a corpse. When you say Phet again, Vajravarahi takes the curved knife and with just one motion your skull becomes a skull cup in front. Then Vajravarahi with the curved knife places your corpse inside the skull cup. Then dualistic mind and negative thoughts in the form of bubbles are purified, and everything transforms into the five nectars and five meats, which is very pure substance. The skull cup becomes as huge as three thousand myriads of universes. The nectar is whitish with a radiant reddish hue. Steam rises from the nectar, which symbolizes the five desirable objects of the five senses. Underneath that skull cup, there are three skull cups, two dry and one wet, which symbolize the dharmakaya, sambhogakaya and nirmanakaya. Beneath that, wisdom fire burns. As it burns, everything within the skull cup heats up, purifying all the afflictive emotions and dualistic mind and impure substances, transforming everything into wisdom nectar that fills three thousand myriads of universes.

Then after saying two Phets, instantly Vajravarahi, holds a golden spoon in her right hand and a skull cup in her left. Then from that skull cup she ladles nectar and pours it, making offerings first to the lamas, and then to the meditational deities, and then the dakinis, and so forth. After that when one says Phet, Vajravarahi makes offerings to all the local beings and the owners of the land, and so forth. And then after saying another Phet, Vajravarahi makes offerings to all sentient beings of the six realms.

As one makes all these offerings, one can purify all the debts and loans and negativities from past lifetimes. After making offerings to all those beings that are owners of sickness, demonic forces, creators of obstacles and negative forces, they are completely satisfied and pleased. In that way by making offerings to all the gurus and meditational deities and dakinis, one could have complete accomplishment and receive all the blessings. And by making offerings to all the negative forces and all other evil beings, they are completely satisfied and pleased. One feels as though all karmic debts have been repaid, and everything is purified.

At the end when one says Phet, then all the offerings, the objects of the offerings, and the offeror, all three, cease to exist and dissolve into emptiness. After that one can do all the dedication and aspiration prayers.