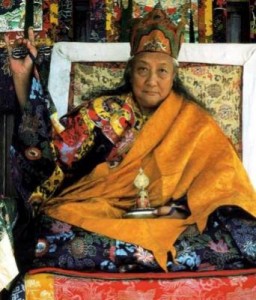

The following is respectfully quoted from “Perfect Conduct: Ascertaining the Three Vows” by Dudjom Rinpoche:

6.b.1(e.4) Restoring through the general cleansing of three yogas:

As is taught in the Hasti-upapraveśya-tantra, the general cleansing yoga of the nest of remorse is the “Stirring the Depths.” By confessing in this way, there is nothing that cannot be purified. Practice this accordingly.

According to the tantra called Hasti-upapraveśya and the Vimaladeśanā contained within it, this is the sole text for practitioners of all three yogas who, having engaged on the path and then allowed their samaya to deteriorate, wish to confess and perfectly restore it. The king of all confessions is Narakakhadāpravāsaprasphotana (Stirring the Depths of Vajra Hell). Here, it is clearly taught that by offering the external gathering of substances, the internal gathering of own’s own aggregates, and the secret gathering of the awakened mind of bodhicitta on the fifteenth, thirtieth, or eighth day of the lunar month, all deteriorations will be fully purified. If that is not possible, but one still makes prostrations and recalls the deity in order to confess, purification will occur. It is important to persevere in this practice as much as possible.

As is said in this text, “To all the enlightened peaceful and wrathful deities and to their mandalas, I pay homage. I pray that I may cleanse all of my broken commitments without exception. There is no doubt that the five limitless non-virtues can be cleansed and that even the lower realms can be emptied from their depths and that beings will be led to the well-known pure realm of the enlightened beings of pure awareness. Since Vajrasattva is the essential nature of secret mantra and cleanses all of our karmic obscurations and obscurations caused by broken commitments, in order to empty the realms of cyclic existence, recite the mantra.”

Accordingly, if one just hears the names of the deities in this mandala, all deteriorations of one’s root and branch words of honor can be repaired. Signs of accomplishing the purification through confession include indications in the dream state; indications from the lama or deity; and dreams of bathing, putting on white clothing, ascending to the peak of a mountain, and the arising of the sun and moon and so forth. Until such signs arise, one should continue to make confession and apply the four remedial powers.

6.b.2 The faults of failing to restore broken words of honor:

If one fails to make confession in this life, extremely unpleasant consequences will ensue. In the next life, one will be born in the vajra hell of irreversible torment and suffering.

If mantra words of honor are left unconfessed, this becomes a cause for rebirth in what is called “vajra hell.” There is no place of greater suffering. As it says in the Guhyagarbha, “If the root or branch of words of honor deteriorate, the result is that falls to the lower realm.”

In the Prakativavictra-tantra, it states: “If a root word of honor deteriorates and no effort is made to restore it, one will fall to the vajra hell. If all the suffering of the ordinary hells were to be combined, that suffering would not equal one fraction of one hundred-thousandth of the suffering experienced in vajra hell.”

It can thus be understood that even an association with an individual who has accrued this degree of negativity can cause one’s own words of honor to deteriorate. Strong adverse effects may occur for those who even come into contact with such an individual. As it says in the Sarvasamudita, “Just as spoiled milk will taint are pure milk with which it mingles, a singe mantra practitioner who has allowed his words of honor to deteriorate can spoils the words of honor of everyone with whom he comes into contact.” Even if one precedes the breaking of samaya by discussing this with others as a means to communicate one’s intention, this too must be immediately confessed. As it says in the Mahānyūha, “If one harms lama, his or her retinue, or the vajra brothers and sisters by casually speaking negatively or by just a subtle sign of dissent, even if only in the dream state, this must be confessed and cleared from the mind. Actual and inadvertent neglect of samaya that remains unconfessed will cause one to fall headfirst into the hells.”

According to these teachings, it is clear that the loss of any root or branch word of honor is a cause for rebirth in vajra hell. However, there are differences in the degree and duration of the suffering experienced, which vary according to the severity of the downfall.

7. The benefits of guarding the words of honor:

With no deterioration, the maximum will be sixteen consecutive rebirths; the minimum will be in this life, at death, or in the intermediate period. Other benefits include accomplishment of the eight common powers; and obtainment of the seven features of a divine embrace. For this purpose, spontaneously accomplish the twofold purpose of self and others.

The words of honor are the source of all noble qualities and are the very support for the stability and presence of such qualities. As it says in the Samānya-sūtra, “Just as the planting of a seed is dependent upon the earth in order for the result to mature, the life essence of the Dharma remains within the words of honor, which fully mature into the unsurpassed state of awakening as the precious life-essence of virtue.”

Temporary benefits include the accomplishment of all that one aspires to obtain; an appearance that is pleasing to all; becoming an object of the veneration of others, including the most powerful worldly gods; and being blessed by the buddhas, bodhisattvas, dākas, dākinis, and all objects of refuge, who guard one like their own child. Having understood the importance of pure samaya by entering the path of all the buddhas, one will quickly ascend the stages of vidyādharahood to realize enlightenment.

If in one’s immediate life one is unable to persevere in the accomplishment of the two stages, yet never allows the words of honor to become defiled, then after taking sixteen successive rebirths enlightenment will be realized. This is the longest possible period of time it will take just through the force and purity of the words of honor alone. After at least seven rebirths, one will meet with the profound path of the two stages and gradually be liberated. The speediest result occurs if one maintains pure words of honor coupled with diligence in the two stages of practice, resulting in the realization of nondual vidyādharahood in that very life. Those of average sensibility will realize the illustrative clear light, which will become the actualization of absolute clear light at the time of their death, and the obtainment of nondual kāya that arises from training. If absolute clear light itself is realized, then at death the nondual kāya (arising from no-training) will be obtained. Those of common sensibility, due to their practice, faith in the lama, and strong aspiration for the pure realms, will be liberated in the bardo (antarābhava) [intermediate state] by arriving in the natural nirmānakāya pure realm.

These are not the only noble qualities that arise from pure samaya. In addition, both extraordinary and mundane spiritual attainments are obtained. The eight mundane spiritual attainments include the power to make an eye medicine, which, when applied, allows one to see without impediment or physical obstruction; speed walking; the sword accomplishment; seeing underground; making power pills; flying in space; disappearing; and extracting the essence. These eight powers are called mundane because they are still of this world and can also be accomplished by non-Buddhists. They qualify as accomplishments belonging to the paths that are both worldly and transcendental. According to Vajrayāna, these qualities are developed during the two yogic states and are thus termed common because they are not the ultimate result. In addition, the eight sovereign qualities are achieved.