The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Western Chod”

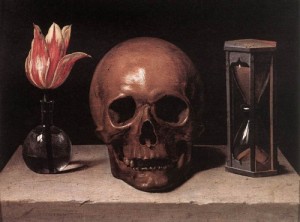

Then I began to examine parts of my body. I thought to myself, “Well, if this absolute nature is the only thing that makes sense, if this absolute nature is the only thing that seems precious and worthy and noble to me, and everything else that I find in this cycle of death and rebirth seems chancy at best, even when it ends happy, it seems to me that it’s nothing to take safety from.” So I examined like that. What about my body? I take a lot of safety from body. After all, if I didn’t have it, where would I be? So I examined my body, and I tried to examine it piece by piece so that I wouldn’t leave anything out.

I remember that I started with my feet. I thought that it was best to start down and work up. So I started with my feet. I really tried to do this purely, and this is my recommendation: If you want to practice in this way, try to do this as logically and purely and as dispassionately as possible. You won’t be satisfied with your practice if you don’t really cover all the bases. It is really necessary to go deeply into this.

So I thought about my feet. I thought, “Well, what can my feet do? What are they good for?” Well, I like shoes a lot. They can wear shoes. So that’s one good thing that feet can do. I can wear shoes that match my outfit. Isn’t that wonderful? Yeah. So what’s the next thing that feet can do? Feet can walk. So if my baby’s crying and he needs me, I can use these things to walk over and pick him up and help him. This is good. Feet are good. We are getting good now. Feet are good. They have toenails on them. We can paint those. They can match my outfit, too. More good news. So what else… We can roller skate with feet. I am personally addicted to foot massage. So we have that. That’s a good thing. Feet can take me anywhere I can go within reason. Within walking distance, feet can take me. They press the pedals on the car. Feet are good for that also. It sounds silly. I went through everything I could think of that feet were good for.

Then I thought to myself, “Well considering all the sufferings in the world, considering what I have thought about already, what I have contemplated, what is it that feet can’t do?” Well, if my child became very ill, really ill, there’s nothing that my feet can do about that. In a way they could contribute. They could maybe carry him to a doctor, but ultimately they can’t really do anything. Then I thought to myself,”Well, if I saw somebody suffering right in front of me, what could my feet do?” Well, they could contribute again. They could take me to that person, but ultimately my feet don’t solve any problems.

I thought to myself, ”Well, these things are really limited then. I really kind of developed a feeling of “so what” about my feet, like non-attachment, like it didn’t seem to me like I should feel about this part of my body as though I were attached. So I thought to myself, “Well, if these feet are so limited, what would be better? What would be better here instead of my feet?” I thought to myself, “If somehow that absolute nature, if somehow that primordial wisdom nature were here in this place instead of these feet, that would be something. That would be something.”

I would actually meditate on my feet, and I would go from the skin to the muscle to the tissue inside of it, to the bones, down to the very cellular level. And I would think, “This I offer to this absolute nature; and I pray that in exchange somehow the blessing of that nature would be here and that where I am, there would be some comfort in the world.” I used to pray that. And every single day I would pray that with such longing because I took time to meditate on the faults of cyclic existence and the nobility and the blessing of that primordial wisdom nature, and I could see the difference. I was so moved. Here in this world there is nothing of that. There’s only the ordinary stuff. I would pray so hard I felt like this whole thing is on my shoulders. I really took this responsibility for everything. I just prayed so hard that somehow this absolute nature would be here.

I felt like I completely renounced my feet. I looked at my feet and they looked like something else. They became to me very foreign. Suddenly I looked at my feet, and I thought, “I’ve given them up. I don’t own them anymore.” If someone were to say to me, “Would you walk over here to help me?” There’s not even any point of saying yes or no. I’ve already offered my feet. They’re going to do it. So I feel this sense of non-attachment, or the realization that my feet are nothing to cling to.

I would meditate like that until I felt really satisfied that I had given these things up. Sometimes it would take a couple of days. Sometimes it would take a week. Sometimes it would take a month for just one element. And I would go from my feet to my ankles to my legs to my torso to my upper body and my head, as well as different external circumstances of my life. Like, for instance, my car. What good is my car? What can it actually do? Drive. Big deal! What can it actually do to benefit the world? That kind of thing. I thought like that.

I would spend this whole time of preparation simply getting ready for what I didn’t know. I really didn’t have a sense of what the work was going to be, but I knew that this was the truth and that it had to be done this way. I really knew that what I was meditating on was the absolute truth.

So I went through all the different parts of my body. In each case, everyday I would not be satisfied to stop my practice until tears had come to my eyes. Sometimes I would really cry. I would sometimes cry for the condition of other sentient beings, or I would sometimes cry that this primordial nature is so noble and yet none us have awakened to it. It seemed so pitiful to me that we are so close yet so far away to this nobility that is our true nature. Sometimes I would cry about that. Sometimes I would just cry as a kind of offering.

I would offer my feet. “Please accept my feet. Please don’t let this be all there is. Please don’t let this be the whole story. It can’t be where we leave ourselves. It just can’t be like this.” So I was crying, “Please accept these feet as an offering. Please, in exchange, let that absolute nature be here.” I would never be satisfied with my practice until I was actually crying or I felt that I had really understood to the depths of my heart that this was the way it had to be, and that this was a kind of necessary generosity that was performed for the sake of beings.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved