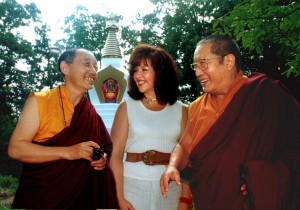

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Western Chod”

Here’s what my practice looked like. At that time I didn’t know that it is better to meditate sitting up, so, I mediated some of the time laying down and some of the time sitting up. I actually found that when I lay down I would fall asleep. So, eventually, I developed the habit of sitting up. So, slowly, slowly, we find our way.

I would set up a symbolic altar. I had a dresser top that I would use for this purpose. I put representations of all things physical. I had some plants, leaves and things like that. I had some food (I think it was fruit generally), andpebbles, rocks, brightly colored things from outside. Then I put a mirror because somehow instinctively I understood. I was sort of in a quandary. I hadn’t had any teachings yet. I was extremely spiritually oriented, yet the only teachings I’d received indicated that God was kind of an old guy with a beard who sat on a throne somewhere. He was making x’s if you were bad and checks if you were good. That was pretty much my understanding of what religion was. I didn’t really buy into that. I really didn’t feel that that was appropriate or acceptable, and it seemed to me just not right.

So my understanding of the divine nature, or what was called God, I had to develop from within myself. I didn’t like to use the word God because I thought that indicated we were talking about something separate. I really thought that whatever that absolute nature is, it is absolute to the point where it cannot be separated from one thing and another. Whatever that nature is, it must be all pervasive. It must be the same nature that causes fruit to ripen or flowers to come forth in the springtime as it is to make my own heart beat. And I really thought that was it. I didn’t know what to call it, but that was absolutely it. So as well as I could understand, I began to meditate on what Buddhists call the primordial wisdom nature or the uncontrived natural primordial view. There are many different ways to describe it, but that was what my meditation consisted of.

My altar had a mirror on it; it had of all these things that represented earth. In my mind that represented all that is form and all that is formless. I didn’t have the word “samsaric” and I didn’t have the idea of things that are contained in the cycle of death and rebirth. I merely thought of things that are displayed in form and those things which were absolute and natural and uncontrived, and I thought my altar encompassed both elements of reality. I was pretty satisfied with that as being something that I could work with.

So, I began my practice. I used to mediate on this absolute nature. I used to think, ”This nature, this nature, what is it? What is it like? What is this thing?” And I would think to myself,

‘Well, this is the same nature that causes flowers to open, the same nature that causes my heart to beat, the same nature that causes my son to be born to me, the same nature that makes people love each other. It must be that this nature is the fundamental foundational underlying reality”. I thought like that.

Instinctively, I understood that this nature was natural and uncontrived. For instance, if we were to meditate or rest in that nature we wouldn’t be thinking, “Oh, I want this or I don’t want that. This is beautiful and that’s ugly.” We wouldn’t be thinking like that. I understood that that nature was some kind of restful state that was spontaneous and luminous, but free of contrivance, free of the distinction of self and other, free of the distinction of good and bad, hot and cold, ugly or beautiful, here or there even. I didn’t even think that in this state time and space actually applied. I realized that this state was free of that kind of defining or discriminating conceptualization. I thought to myself, “This is the underlying reality”.

When I meditated on that state, I knew, or I tasted, that upon holding the mind in that natural restful state free of contrivance, free of discrimination, there was no potential for suffering in that natural state, because nothing that causes suffering was there. Grasping and desire weren’t there, hatred wasn’t there, selfishness wasn’t there, anger wasn’t there, ignorance wasn’t there. We meditate on that state; we are not blind to that state. So, I didn’t feel like there was ignorance there or dullness or any of those things that cause suffering. I felt we were not inherently there in that nature.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved