An excerpt from a teaching called Compassion, Love, & Wisdom by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

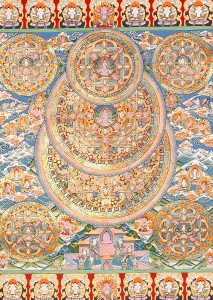

Ordinary sentient beings cannot bring about extraordinary ends. Ordinary sentient beings do not have the skill to bring about the end of suffering, since they themselves have within their mindstreams the causes of suffering. Who then will act as this guide? Who then will bring this path? Who then will offer these teachings? Who will announce a door to liberation? It must be our intention as we practice this path until we reach supreme enlightenment, and once having accomplished realization, that we will remain in such a form as a Bodhisattva and return again and again and again in order to benefit beings. This is ultimate compassion. This is the compassion that is actually quite different from ordinary human kindness.

Let’s take as an example a relationship with a teacher. Let’s say that you have found a teacher who has those qualities, who has attained some realization and returns again and again to benefit beings. We might think of human kindness in a certain way. For instance let’s say that I have a student over here and he is a little slow. He is a nice person, he is trying to accomplish Dharma, but he is a little slow. Well if you examine it, that slowness is the result of laziness. He is a little lazy. Maybe he doesn’t have all the compassion he needs to really be fervent on this path. Maybe he really needs to develop that compassion and maybe he is just getting a little slothful and maybe there are some things that the teacher can see that are not quite kosher, not quite right with him. But because we are ordinary we might think, well maybe he is just a little slow and he can’t help it, he is doing the best he can. He is a nice guy, just leave him alone. He is a little slow. We might think maybe we will just be kind to him and we will try to support him to see if we can help him. Then we will just be nice to him and little by little he will do the best he can in his feeble, little way.

So he continues and he is still kind of slow and feeble and pitiful. Then one day a good teacher comes along, sizes up the situation and really displays some wrathful activity and says, “You are going to straighten up your act.” Gives him ‘what for,’ tells him the truth, reads him the riot act, testifies before Buddha and just changes his whole life around. Causes him a great deal of upset, causes him to have serious gastric disturbances, causes him to whimper and cry a little bit and the rest of us might think, poor guy, boy did he ever get it. Wow, that is really rough, that is really terrible.

The difference is that this teacher might have had the capacity to understand what is really happening is that an obstacle to his practice is arising. It isn’t about being simple at all, it’s about an obstacle to his practice arising, and that obstacle has to do with past habits of sloth and laziness. It has to do with not having been helpful to other sentient beings; it has to do with his not sending his mother a card on Mother’s day for a couple of years. We couldn’t see what the Lama could see and the Lama knew, but the Lama had that kind of wisdom. Well, what happened to this poor old guy is that he got really shook up, he got finished with his serious gastric disturbances, he took him pepto bismal and he is all squared away. Now suddenly he has changed.

How has he changed? Has he changed because he really needed to be yelled at? No because you could have done that. What the Lama did was to cut out an obstacle and that is kind of miraculous activity because there was awareness there, there was a skillful means that ordinary sentient beings don’t have. There was also a pure motivation. That Lama wasn’t really interested in yelling at this poor guy, but he saw there was an obstacle close to the surface and if it were cut out in some profound way it would be pretty clear sailing after that. That is also possible. I don’t know if there is such a Lama or such a situation, I don’t know if any of these things are true, but I do know what I am describing is the difference between ordinary perception and extraordinary perception, the difference between ordinary human kindness and true compassion.

Human beings want to follow human rules; we want to be kind in the ways we are taught. We think that is the answer because we don’t understand cause and effect. We don’t understand that in order to change the effect we are seeing now you cannot simply mess around with the effect some more. You have to remove the causes. If you have that pristine awareness, if you have that awakening, if you have that quality of knowing that comes with that kind of realization, you might be able to see the causes. Through skillful means, with pure enlightened intention through the perfect stability of the union of wisdom with pure compassion in your mind, you might be able to bring about the causes to end the particular suffering he is experiencing. So maybe the man turns around and maybe it’s not because of the reasons that you think.

Our job is to develop these extraordinary skills, and although I think in my case it is going to take an awful long time, still I think we have to do our best to understand that what is needed to accomplish the end of suffering are not ordinary techniques. They must come from the mind of enlightenment, they must lead to the mind of enlightenment, they must exhibit the qualities of the mind of enlightenment and they may not be exactly sympathetic to some of the human beliefs we may hold true. We have to accept that this may be a challenge for Westerners. Ordinary human kindness cannot be discounted. It is a part of what we must do. Actually ordinary human kindness is included in the miraculous compassion I just described, as not only did the Lama have the skill to know what was wrong with this fellow, not only did he have the ultimate compassion to care deeply that he accomplish his practice and achieve supreme enlightenment, but he also had ordinary human kindness. He cared about the guy and wanted him to be happy.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo