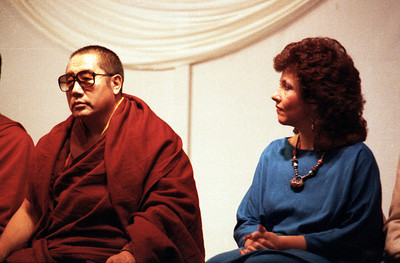

An excerpt from the Mindfulness workshop given by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo in 1999

When I first met His Holiness Penor Rinpoche, he came to where I was in Kensington, Maryland, and wanted to stay at our house. I had only met one Tibetan in my whole life. I had no idea what a Tibetan lama even was. I had no idea what to do with a Tibetan lama. Where do you put them? What do they eat? I wasn’t being silly, I just didn’t know. So I thought, “Well, we’ll have a barbecue!” I didn’t know what to do.

I remember it, and I think about the way I was then. Of course, it was natural, but there was His Holiness sitting on a bench! I remember plopping down right next to him and asking casually, “So, what do you think of the barbecue?” If I did that now, my head would explode! Thankfully, some spiritual discrimination has been developed since then!

During that visit, His Holiness said he wanted to talk to all of my students. He wanted to ask all of my students, “What does she teach you? What do you know about this, that and the other thing? What do you think about compassion? What does she tell you to do? How does she tell you to practice?” He questioned all my students, and I hadn’t even talked to him alone yet. I didn’t know that you were even supposed to ask Tibetan lamas questions. I just didn’t know.

I saw that when he was interviewing my students, they also had the opportunity to ask him these great questions, and he gave them these really cool answers, about karma and how things are and why things were, and I thought, “I’d like a chance. Give me the opportunity.” I asked His Holiness if I could come and talk with him, and he agreed. So I went in and I talked to him and I said, “Rinpoche, when I first saw you, I knew that you were purity itself; that there is nothing more pure than you. So based on that, I’m asking you, at a certain age it just came to me to start teaching like that — teaching about emptiness, teaching about compassion, teaching about benefiting others, but I wasn’t taught this. Until you, I didn’t have a teacher in this lifetime. How can this be? Have I done something wrong?”

I told him I felt like there were two justifications for me to teach before I had met my teacher. One of them was that when these practices, like the natural kind of Chöd that I was doing, came to my mind, and I did them, they worked. I could feel the renunciation that was happening. I could feel it. That was one determining factor. I could feel that when I spent a large percentage of my time trying to be of benefit to others, I could feel that it worked. I could feel that it made me happy. So I began to practice like that, and I felt that I was authorized to teach others because I practiced it and I could see that it worked.

The other thing was that I looked around — ever since I was a child I could see that there’s nothing but suffering here, that suffering is all-pervasive, and even when it’s temporarily alleviated by some kind of temporary happiness, it’s all-pervasive and it returns, and the suffering is primarily spiritual. I told His Holiness, that being the case, I felt I couldn’t wait. I felt that if I knew something, anything, that would help, I’d better do it. I asked him how these things have just come in my mind: this practice of generosity, this meditation on emptiness, this Chöd, where does it come from? And by what authority am I passing this out? How is this happening, and why doesn’t it happen to everybody? And he said to me, “You were a bodhisattva in so many past lifetimes and you accomplished your practice — and he spoke of mindfulness and awakening and stuff like that — you accomplished your practice to the degree that it is mixed like milk with water into your mindstream. You are not separate from that. In every future lifetime, when you appear, you will remember the teachings. You’ll remember them because you practiced them so mindfully.”

Do you hear what that tells you? I’m not different from you. I use deodorant. I stink when I sweat. I am not different from you. That tells you that, according to His Holiness, a Living Buddha, this practice of mindfulness is so potent, so perfect, that if you really invest all that you have into it in an honest and deliberate and profoundly deep way. You can take it with you! To think that that is the one treasure, the only treasure we can take with us when we die. You can’t take your car, you can’t take your TV, and you can’t take your boyfriend or girlfriend, husband, wife, or kid. Even if you and your whole family die together, you can’t take them with you. It doesn’t work that way. But that profound Recognition, that habit, the constant making of that habit of Recognition and mindfulness, that you can take with you.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo