An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo on October 18, 1995

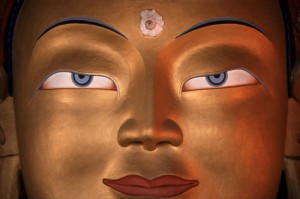

When we meditate on Buddhahood or contemplate on what it would be like to achieve realization, what do we think we are after? What do we think the result will be? Eventually, through the force of our practice, we are hoping, (and if we practice well, this will surely be the result), that someday we will awaken as the Buddha has awakened. So we are actually looking to give rise to the very same thing that we are looking at when we see the Guru. We are looking to give rise to the primordial empty nature. We are looking to give rise to this nature which is free of contrivance, free of distinction; this primordial empty nature that is the innate nature, the Buddha nature. We are trying to give rise to that in such a way that it appears, even within samsara. We wish to attain realization now. So it is that very union of emptiness and display, of emptiness and luminosity, of wisdom and method that we wish to give rise to in our practice. This is the very ultimate object of refuge.

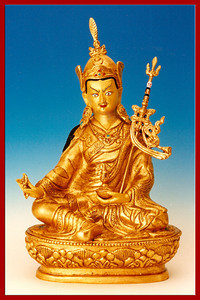

From the Vajrayana point of view we are told that realization will never happen without the necessary ripening that is provided by the root Guru. We are told that in our practice we are dependent upon the root Guru to transmit this blessing and to lead us through the door of liberation. But we must understand that it is more than that. Practicing devotion in the way that we do opens the door, creates the connection, creates the habit, creates the karma, creates the cause by which we will awaken to our own primordial wisdom nature in the future. And that nature will appear in samsara as the enlightened appearance. This is the goal. This is the very wish. Understood in that way, the Lama then becomes even more the center of our mandala – the mandala of our practice, of our hope, of our prayers, of our devotion, of our lives. The Lama, then, becomes the very core of our lives.

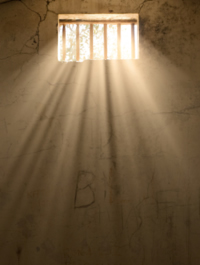

You must understand that there is never a time that you are not in the presence of the Lama. Not for a moment is there a time that you are not in the presence of the Lama. If you refuse, if through ignorance you doubt, if through habit you ignore, if through slothfulness you simply put no effort into accomplishing that view, then you are not actually turning away from the Guru “out there.” This is not an act that is happening between you and somebody else. You are not slighting the person that is sitting on the throne. That is not what is happening. What is happening is that you are turning your own mind away from the very face of your Enlightenment, away from your nature. You are splitting yourself away from salvation. You are wrenching yourself away from the very hope that will bring future happiness and realization. You are cutting yourself away from the root of your accomplishment.

Now that I have told you this, you cannot in good faith and good conscience remain superficial in your practice any longer. You must understand that every moment that you say, “Oh, well, I can do this,” or every time you push away the Lama in order to live in your ordinary samsaric mental posture; every time you do that, you are spitting in the face of your own Buddha seed. You are turning yourself away from primordial emptiness, from the Buddha nature, from the pure luminosity that is the very display of that nature, that luminosity that we also know as the Bodhicitta. So then you have abandoned the root of your accomplishment. You have abandoned the very milk of your nature, and you have shut the door to the great Bodhicitta. That is what we do when we forget and deny that we are always sitting at the feet of the Guru. We are always looking into the eyes of the Guru. And so, we have to train ourselves to keep the Guru above the crown of the head, on the throne within our hearts, in our eyes, in our ears, in our hands. We have to train ourselves as though we were some kind of precious vessel that was carrying around this most precious nectar of Enlightenment. We can’t spill a drop; neither can we turn away from it. And we’ve spilled so many drops already.

But now we know what we have in our hands, and like practitioners that have perhaps moved from childhood to adulthood, we can now expect ourselves not to drop the ball, not to drop our practice, whereas before, we were like children. You know, when you teach children to prostrate, you do not worry whether their form is perfect. When you teach them to say mantra, you know they are going to make mistakes. But now we’re moving past that regarding our devotional yoga. We can no longer allow ourselves to be the children that we once were.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo