An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Dakini Workshop

When the Buddha’s activities are accomplished in the world, through our lack of understanding, we will see lots of different things. For instance, in this temple, we may see the need for fundraising, and we may see the intensive effort that is supposed to go into that. We may see the need for expansion and how intensive the effort for that can be and we may see the extent of our own effort, which seems to be awesome. Yet, every bit of that perception is only based on the belief in self-nature as being inherently real. There is no one to struggle if the belief in self-nature is not clung to. It is that clinging that is the basis for the struggle.

From the point of view of enlightened intention, one can understand that from a tiny event that seemed in our continuum to take place 2,500 years ago and then continued on with a thread of different experiences and different incarnations, it may seem that that tiny event gave birth to the oddest things in the oddest of places in Poolesville, Maryland where the Dharma is born. Then we think about all of the things in India and we think about all the things in Tibet and we think about all the things that are happening around the world concerning the Buddha’s activity. From the point of view of the intention of that one life, that is a very small piece of effort. But from our point of view, of course, we are seeing the great effortfulness and it seems to be continuing endlessly, especially within the context of our lives. We seem to think that it is continuing endlessly.

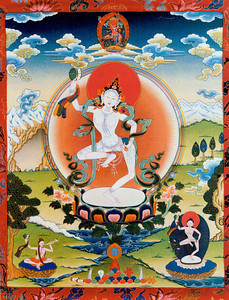

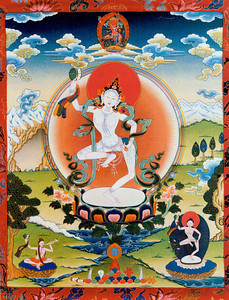

One must understand, however, that even thinking that all of this came from one small life, even that is an outrageous delusion. It is a contrivance that we make to satisfy ourselves. One must understand that from the point of view of enlightenment, from the unborn vast expanse of emptiness, of blissful emptiness, within that sphere of truth that we call the great mother, all potency spontaneously arises and is born, demonstrates itself or dances or moves in as many displays, forms, formlessnesses as we can possibly imagine and beyond what we can imagine. And even as it is born, even as it moves, it is inherently and therefore immediately complete. That means that all sentient beings have within them the inherent Buddha nature and therefore will achieve enlightenment, but that is our confusion. In fact, we have never been separate from the sphere of truth. We have never been anywhere else but born and completed in the great lotus of the great mother. Anything else is complete fabrication.

We have never left the space of emptiness and we have never lost the scent of emptiness. From the point of view of enlightenment we have never beheld or looked at anything other than emptiness. We have never seen anything other than our own face. We have never lost a moment’s time.

Yet, here we are trying to understand the nature of the dakini, like trying to be seduced back into remembering our own face, straining to hear the sound of our own name. From the point of view of the enlightened activity that is consistent with the dakini nature, there is no loss. There is no distinction. There is no separation. There is no need for struggle. Yet it is clear that we remain fixed on the idea of separation between self and other. We remain hooked with concepts such as the distinction between dirty and clean. We remain addicted to the idea of hatred, greed and ignorance and seem to be unable to let them go so that they can simply do what they do naturally so that all phenomena, the moment that it naturally arises, is immediately completed.

From the point of view of enlightenment, no phenomenon continues itself. No piece of what we experience, whether we wish to experience or do not wish to experience, by its nature continues or completes itself. The experience of continuation that we have is only due to our own continuing it, our own determination to continue it. No phenomenon is exempt. All things arise from the sphere of truth. They are spontaneously born and instantly complete.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved