The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Marrying a Spiritual Life and Western Culture”

I don’t know how many times I can present this same teaching. It’s about understanding that the ball is in our court. It’s about having a direct hands-on experience, not about being a good boy or girl. Aren’t you sick of that? This moralizing stuff has got to go! Instead, have a direct understanding, a natural wisdom—your wisdom—that dry times cannot take away from you, that broken hearts cannot take away from you, that no one else can take away from you. Your wisdom. You don’t look to anyone else to get your wisdom. You’ve got it inside. You understand the path in a deep way. You are empowered.

I’m not talking about ritual empowerment. I’m talking about a deeper, truer kind of empowerment. How wonderful if we can know that spiritual empowerment deeply within ourselves, to then go through the process of ritual empowerment according to the teaching and know what it’s about. It’s not just a vase (or a bhumpa) being knocked on your head. You could do that from now until your head and the bhumpa are both flat, and there would be no direct relationship. If it’s all academic and intellectual, then it’s the same as getting a Ph.D. anywhere in technical sciences or whatever. It’s not really a path. A path is a way you go. A path is not an object that you consume or collect or put in your crock pot and boil all day until it makes gravy at night. A path is where you are. Where are you then?

What I’m talking about is carefully considering how to overcome the limitations of confinement of our kind of society, of our kind of culture; how to go more deeply to have a more direct relationship with our own spiritual nature—a real mystical relationship with that nature. And I don’t mean just meditating on some sort of internal cartoon circus where you think you’re getting messages from the Pleiades or some baloney like that. If you had a real, direct relationship with your own nature and you really understood the wisdom and the beauty of the Buddha’s teaching and didn’t see it as his teaching, but as a wisdom that appeared in the world here, you could see it as your teaching, as a wisdom that you could connect with.

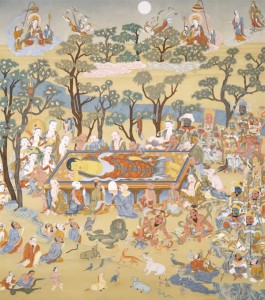

Actually, we Westerners have a similar problem to what Black Americans have approaching Christianity. Black Americans pray to white Jesus. It’s not to say that their faith is small. I don’t know whether they have a problem with it or not, but it must be odd. What does it look like seeing a white face on an altar when you’re a black person? Go home and look at all those Asian faces on your altar. They don’t look like us. What to do about it? How do you take refuge? How do you connect? It’s not about those pictures. It’s not about those faces. It’s about you! And it connects inside.

It isn’t about the shape of those eyes. It’s about what those eyes see. So you have to have that completely personal relationship where you look beyond that which is slanted or colored or this way or that way. It’s got to be a deeply personal relationship. To do that you must connect deeper than you’ve ever been before. We love to just skate over the surface of our experience of life. We’re even addicted to the highs and lows.

You can’t really understand why and how to take refuge by learning a set of equations or laws or rules. These can only function as guidelines. It’s really up to us to be powerful and strong and noble and knowing and awake on our path. Virtue cannot be collected. It has to be experienced, tasted, understood. Its nature must be understood.

This is not the news we want to hear. We want an easy religion. We think, “Just tell us the ten things we have to do so that we’re not uncomfortable about dying.” I’m not saying those ten things are bad; they’re good, they’re wonderful. But where does it lead you? Aren’t you still the same scared little kid who was so neurotic because you are compressed with rules and society and with being told you can’t feel things. And now we’re going to do this with our religion too. Ten more times.

What if, instead of being a girdle that makes us out of touch just trying so hard to be good, we experienced our path—our method—in a wisdom way, in a connected way, in an in-touch way? From that fertilization that happens when you really understand an idea and it causes you to go, “Ah-hah, therefore…”, from that point of view it’s like a plant or a tree coming up inside of you and growing. It bears fruit. It is a joyful thing, and you can see the fruit of your life. Most of us are so unhappy and so neurotic because we cannot see the fruit of our life and we do not understand its value. We haven’t tasted it. This direct relationship one can taste. It needs to be like that in order for us to really take refuge and not be lost little kids scared of dying, just trying to do the right thing—be good boys and good girls with a new set of rules—because maybe if we just had a new set of rules, maybe then we’d be good.

Instead of that, what if we were dynamically in love, inspired, breathing in and out on our path? The path can, in that way, be a companion, a joyfulness, a child of yours, a creation, a painting, something beautiful you’ve done with your life. You can’t make a beautiful painting by number. You have to make a beautiful painting from your heart.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved