A Teaching from Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

Three thousand years ago Lord Buddha introduced the idea of great compassion to an unknowing world. After his enlightenment he was asked to teach others the means to supreme realization. Although he was tempted to simply leave — knowing that almost no one would be interested in his teachings, and of those who were, few would try to follow them and fewer still would succeed — he nonetheless replied, “For those few, I will remain.”

Buddha is the exceptional teacher who teaches the development of great and selfless compassion as part of the technology of the path to enlightenment. But to develop such great love, it is first necessary to familiarize oneself with the nature of suffering and especially with its causes. Amidst the array of spiritual teachings, this perspective is unique because most people do not understand the reasons for suffering or how suffering appears in the world.

The Buddha taught us that human happiness through ownership, eating, drinking, gaining love, stature, approval, or even the happiness of engaging in pleasurable activities is at best temporary. These experiences do not prevent suffering because between these happy times we can experience times of distress.

Nor do happy times solve questions concerning the nature of suffering and why it arises. The Buddha taught that the happiness of enlightenment is not composed of impermanent things but occurs when one cuts out the sources of all unhappiness. Through understanding and meditation, one liberates the mind into true awareness, a state free of conditions and defilements. This pure awareness is a lasting state.

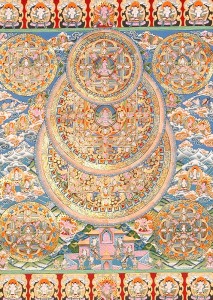

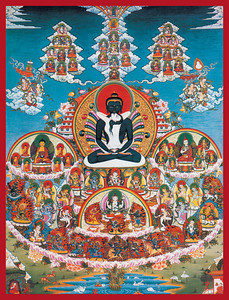

Ultimately, the attitude of care-taking or being responsible for the wellbeing of others, of caring for planet earth, its inhabitants and all the 3,000 myriads of universes described in Buddhist cosmology is the true cause for ultimate and permanent happiness. Being responsible for all sentient beings is a spiritual technology the Buddha taught to be the supreme antidote to selfishness, compulsive desire, self absorption and all other symptoms of the ego.

When we remain selfish and neurotically fixated in the ego, we remain deeply unhappy. When we are in a state of profound generosity, having a relaxed mental attitude and pure motivation, we remain stable in a state of joy. Yet if we view caring for others only as a medicine, we may miss the beauty of it.

No sentient being is born with pure, unconditional, constant love. In the beginning, selflessness and generosity require discipline. Like all things, they must arise from a cause. One must break old habitual tendencies, and this requires discipline. Initially, one must understand the values of generosity and the pitfalls of selfishness. One cannot then rely on one’s feelings, because they are products of an ego distorted by the self-centered habits that produce unhappiness and disregard for others. It is necessary to understand the cause and effect relationship here.

Happiness does not just appear. Enlightenment does not just appear. Neither do unhappiness or suffering just appear. When one understands this apparently simple truth, it is possible to make generosity part of one’s activity in a true and lasting way, because one has a basis of understanding that will support and uphold the discipline necessary in the initial stages.

Ultimately, through persistence one can soar. There is a point at which a great leap takes place and one moves into an experience of effortlessness. This is because ultimately, in the pure state, compassion is part of one’s nature. We each, in fact, live in a world of our own making and have the choice of living selfishly, trying in a futile way to get happiness through gaining or having more phenomena (whether external or internal) or we can live a life of generosity and responsibility, cognizant that there are many more sentient beings than just our selves.

Because their value is equal, many pieces of gold are worth more than a single coin. So it is with sentient beings. Many are more precious than one. Fortified with that awareness, one can live and act accordingly with simplicity, generosity and respect for life. The attitude of cherishing all sentient beings as though they were truly the same as you is a deeply moving and personal experience. It is a life changer. It is also the cause of happiness.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

![buddha-wallpapers-photos-pictures-autumn[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/buddha-wallpapers-photos-pictures-autumn1-300x224.jpg)