The following is a brief history of Kunzang Palyul Choling:

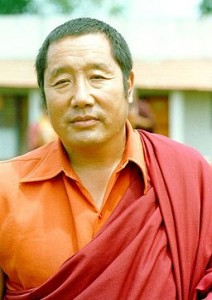

Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo

Ahkön Norbu Lhamo

The following is respectfully quoted from “Reborn in the West” by Vicki Mackenzie:

After Penor Rinpoche had left, the group dwelt on all that had happened and what he had said. Dutifully they began looking for a property, and sure enough, they found a beautiful place which would suit their purposes perfectly. It had white pillars all along the front. But the price was astronomical. Scraping together whatever money they could, and taking out a huge mortgage (which now necessitates many ingenious fund-raising schemes), they bought what is now KPC and established what over five years later has become the largest ordained Tibetan Buddhist community in the USA. Every Sunday over 120 people came here from the surrounding area to hear Jetsunma’s teachings.

At this stage Jetsunma still didn’t know precisely who she was. That was still to come.

A year after Penor Rinpoche’s visit Jetsunma felt the urge to see again the small, round man who had come into her life and touched her so deeply. She decided to go to India, to his monastery in Bylakuppe in Karnataka state. For the girl from Brooklyn who had never set foot outside the USA, landing in Bombay with its chaos, colour and poverty was merely a prelude for the greater revelation that was to follow.

Facing Penor Rinpoche on his own territory, she said she wanted to take the bodhisattva vows. This is the ceremony in which you formally promise to dedicate your life to the well-being of others. She asked if he would give her a spiritual name, as was the custom at such an occasion.

‘When the time is right,’ replied Penor Rinpoche.

‘When will the time be right?’ pushed Jetsunma, with typical Western impatience.

‘I’ll give it to you when the right day comes,’ continued Penor Rinpoche.

‘When is the right day going to come?’ persisted Jetsunma, not giving up.

‘When I say so,’ retorted Penor Rinpoche firmly.

Jetsunma gave up.

One day, when the moon was in a particular place in the heavens, Penor Rinpoche called her to him and announced: ‘Now I am ready to give you your name.’

He then wrote out her spiritual name on a piece of paper, rolled it up into a scroll, put his personal seal on it, then handed it to her with the white katag (scarf) of respect wrapped around it. ‘That’s your name–Ahkön Norbu Lhamo,’ he said.

There was no apocalyptic vision, not instant flashback to another time, another place, another body. There wasn’t even shock or surprise. Just a sense of intense familiarity.

‘I experienced serious dejà vu,’ was how Jetsunma recalls the occasion. ‘I felt a strong connection to that name. I asked him to say it again. It was like milk to my ears.’

Through his translator he then uttered the monumental words: ‘I now recognize you as the sister of Kunzang Sherab. Her name was Ahkön Lhamo. In that life she and Kunzang Sherab co-founded the Palyul tradition. I recognize you as her incarnation.’

And in those few simple sentences Penor Rinpoche made sense of the extraordinary life that Jetsunma had teched out for herself and the otherwise inexplicable abilities she possessed. This, at last, was the official explanation of how a woman with no Buddhist training whatsoever, no books on Tibetan Buddhism, no teacher, no outward example to follow, had been driven to enter years of strict meditation by herself and to emerge with not only profound wisdom but also the wish and the ability to help others fulfill their spiritual potential.

Understanding Duality

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Art of Dispelling Anger”

So what happens in the awakening? Well, we’ve worked with our poisons sufficiently. We have some inner knowledge and honesty. We’ve worked some method and now we’re accomplishing view. That’s where we really start to get cooking is where we practice the view. The view is—I love this part—every woman you see is a goddess and I’m the queen. We see that all beings are Buddha. We see that the females, whether they look like goddesses or act like goddesses, are goddesses in their nature. They are Tara. They are, as are you, the primordial pristine state. We look at men, and rather than list their faults, which most of us do, we look at them and think, ‘This is Buddha. When you think of your husband, your child, your friend, your enemy and even President Bush, you think, ‘Yeah, this is Buddha, in his nature.’ And when we look around and we see that the appearance in relative view doesn’t look like Buddha, we shouldn’t take that as proof that the teaching is wrong and that we have a good excuse to hate. We should take that as a reasonable display of the fact that we are lost in samsara. Here we are in our nature, the very Lord Buddha. When we awaken, we are Buddha. And yet we are in prisons; we are in hell realms; we are in abusive situations; we are hungry; we are angry; we are at war; we suffer. And yet we are the very Buddha we aspire to follow.

In Buddhism we are taught there are the ground, the path, and the fruit. All three must be present in order for liberation to be possible. And this is one way in which we understand our natures. The ground is the basis of accomplishment. If you did not arise as phenomena from the fundamental primordial self-luminous view, if you did not arise from that, if you were not the very bodhicitta in its display form, if the Buddha seed did not rest within you, if it were not so that each and every cell of your body is replete with the entire mandala of peaceful and wrathful deities, if that were not true, there would be no basis for accomplishment. But in our nature, we are Buddha. That is the basis.

And then there is the path. The path is as important as the basis, because while we have the Buddha seed, we may not have method or a way in which to awaken to that or to bring it forth. A fly is Buddha. He also arises in the display of duality in the samsaric world; and yet his nature is Buddha. His nature is the very same, no different. We each of us stand in the presence of our root teacher, whether it’s in our private practice or whether it’s here at the temple, and we could be a fly. But the difference between you and the fly is the fly has no method. The fly cannot practice method. The thing he is doing is not prostrations. He’s wiping his thighs or something. So we have to apply method. That’s what the Buddha’s teaching is all about. It’s all about different methods at different stages for different people.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Beginning Spiritual Training

The following is respectfully quoted from “Reborn in the West” by Vicki Mackenzie:

‘There was no one to put me in touch with Buddhism. Not at all. The only thing that could have connected me, but didn’t, was that my mother took me to Coney Island and a palm-reader there told me I was an old Tibetan. That was all. I had no idea about Tibet. Not a clue. When I thought about Tibetans I thought of smelly old men on rugs!’

When she ran away from home on the advice of the police she headed for Florida, where she met a man, and married him. She had a baby and they moved on to an isolated farm in North Carolina. That was when Jetsunma’s spiritual story began. Finally away from the hubbub of city life and the distress of her own family situation, the greatness that was lying within her began to evolve. Without any particular emotion or even interest in her voice, she explained the extraordinary series of events that followed.

‘I started to have a series of dreams–I’ve had odd dreams all my life. And in these dreams I would be told what to do. A succession of very strange things happened.

‘Most of these dreams told me to look for a sign. The first involved meeting a an old woman, she was like a witch in a turreted castle. This woman placed a circle on my forehead and said, “This is who you are, now you have to commence.” Three days later a friend of mine asked me to go with her to this woman who did astrological charts, which interestingly are drawn in a circle. We thought it would be a bit of a lark, and so we went. This woman opened the door and, as surely as I’m sitting here, she was exactly the same as the woman in my dream. She had the same face and was wearing the same clothes. I remember breaking out in a sweat!

‘She was really old, but somehow I was very attracted to her. I remember looking at her and thinking she was beautiful. Anyway, she said she wanted to do my chart. After a while she came back and said, ‘My dear, I have nothing to say to you. Your whole life is laid out, you don’t need any advice from anybody.’ I think she was very skillful because she didn’t crystalize anything–she let it stay fluid.

‘Three days later I had another dream which showed me the farm where I was living, but there were extra cars outside the porch. A thunderstorm blew in, and the sky was unusually green. Well, three days after this dream–it all seemed to be happening in three-day-periods–I’d gone out shopping and come home with some friends in their cars and the thunderstorm happened. In the dream the voice had said, “When you see this, it is time to begin your meditation.”‘

To say Jetsunma was taken aback would be an understatement. She was just nineteen years old at the time, and wondered why these things were happening to a poor ‘girl from Brooklyn’. Furthermore, she had no knowledge of or training in meditation.

‘I went out to the front porch and looked at the scene to make sure it was exactly like my dream. It was. Then I went back into my bedroom and lay down! I knew that if I prayed for guidance I would get to learn how to meditate, as the dream had instructed. That was the start of my real spiritual training.” she said. It was to be highly individual and quite unorthodox.

‘The first thing I was “told” was that I had to make a very deep commitment that everything I did from here on would be a channel for blessings. So I use to do this meditation where I would say things almost as if I were chanting a mantra: “I commit myself to benefitting all beings, my life has no meaning other than the benefit of all beings.” Unbeknown to her at the time, she was uttering stock Tibetan Buddhist concepts in stock Tibetan Buddhist jargon. Every day she diligently continued feeling her way along her meditations.

‘The picture I had was of being a faucet–the water was in there, and I just had to turn the faucet on, kind of thing. I tried to align myself with the principle of broad-spectrum compassion.”

Meeting Her Teacher

The following is respectfully quoted from “Reborn in the West” by Vicki Mackenzie:

I spent a couple of days at KPC admiring the grounds and meeting some of Jetsunma’s followers. One of them was Wib Middleton, a friendly, open man who was one of Jetsunma’s earliest students and is now the chief administrator. I asked him for his impressions of this first female Western tulku as she ventured out on her mission.

‘When we met her it was 1981 and she and her family had moved to Washington. We were really drawn to her. We were a group of seekers, about ten of us, New Age-type people who felt there was a lot more to life and who had an innate sense of wanting to contribute to society. But we didn’t have a vehicle for that. We looked around, but a lot of the New Age stuff seemed to be so self-focused and self-centered. When we met her she had a very expanded way of talking about things. She talked about “planetary consciousness and planetary quickness” and the “vibrational zero” which was her word for emptiness. It was really amazing stuff,’ he said.

‘We went and asked her to teach us, and said said “Sure.” So we began meeting in living rooms about once a week. She started teaching us meditational practices and we’d have discussions which she would lead. Looking back, I can see that she was addressing the specific needs of people around her,’ he said.

‘Although she taught confidently, as though from an inner authority, she never made claims for herself in terms of what her abilities were,’ he continued. ‘She has never done that. In fact, she has always publicly refuted the idea that she has any special qualities at all. She was always very humble. She says things like she is not a very good teacher, that she has no particular abilities. Still, we could see that she had developed certain inner qualities and crossed certain lines of consciousness,” Wib said.

If Jetsunma’s spiritual life was accelerating, her material life was deteriorating quickly. Money and physical comfort were in extremely short supply. She and her family were living in a one-roomed place with crates for furniture. She had steadfastly refused all payment for her meditation classes and was working in the clothing department of a big store while her husband was trying to find a teaching job. When things got really right, Jetsunma announced that she was thinking of returning to North Carolina where her husband had the chance of a teaching position.

‘When we heard that, we went crazy,’ said Wib. ‘We thought, “This is our teacher, we need to keep her around.” The group had grown to about a dozen or more. Late one night we dashed over to her place, knocked on the door and said, “Look, here’s the deal. We’d like to start formal classes. We’ll pay. We’ll start an organization, and the organization pays you.” She replied, emphatically, that she didn’t want to be paid to teach. We said we’d worked it out so that it wasn’t like that. We’d have an organization with a board of directors and we’d take care of it. And that’s what we did. We started formal classes and an organization called the Centre for Discovery and New Life. We had a little logo and a board of directors,’ he recalled.

After that the organization grew organically. Soon there were two classes a week, then three. And all the time the teachings that Jetsunma was giving were becoming deeper and deeper.

‘Every week it would be more mind-stretching, more amazing than the week before. We would walk in and think, “There is no possible way that the information she is going to give us could get more profound”, but it was. She was teaching about the nature of mind, the void, different subtle bodies. At that stage we were between Western metaphysical language and Eastern concepts. We certainly weren’t calling ourselves Buddhists.’

The teachings continued pouring forth out of Jetsunma–week after week. Little did the group know it then, but they were all being prepared for what was to follow. “When it happened, they didn’t notice it at all.”

‘One of our friends introduced us to a Tibetan called Kunzang Lama from a monastery in south India,’ continued Wib. ‘He came to our centre on a rainy night with a lot of carpets he was trying to sell to raise money for the monastery. He also had a book of pictures of small Tibetan kids–mostly young monks who needed clothing, books and food. At the meeting we decided to take them on as a project. None of us knew anything about Tibet and we knew very little about Buddhism. Our knowledge was restricted to Vietnamese monks burning themselves–and there was some confusion with the Hare Krishna movement! It was the typical American response to somebody else’s culture and religion,’ he said, laughing.

Entranced by the pictures of the little monks, they realized there was an excellent opportunity to put Jetsunma’s teachings into practice. ‘Right from the beginning she had emphasized compassion, seeing suffering and doing something about it. She said that suffering came about because thought of ourselves as “separate”. She talked about “union consciousness”–recognizing that there’s one operating principle–and that the one way to understand our own and everybody else’s nature was through love and kindness. She talked a lot about “stewardship” and “caretakership” of the earth and all the creatures on it.’

Within two or three weeks of the carpet-seller’s visit they had managed to sponsor seventy-five children back in south India, and a rewarding correspondence followed. They learned what the little monks were doing and discovered it wasn’t so different from what they were doing in Washington. They also learned that the abbot of the monastery was called His Holiness Penor Rinpoche, who was the head and 11th throneholder of the Palyul lineage of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism.”

The tale fast-forwards a year to when the group received a letter from the carpet-seller saying that Penor Rinpoche was making his first-ever teaching tour of the United States. He wanted to visit Washington to meet and thank the people who had generously sponsored so many of his young monks.

The group was delighted, but had no notion of who or what Penor Rinpoche was nor how to treat him. By this time Jetsunma had moved to a bigger house because they could no longer fit into her living room, but she was still doing everything herself, including all the cleaning, setting out chairs, organizing the coffee and snacks, and of course looking after her family.

Penor Rinpoche arrived in spring 1985. When the group went to Washington Airport to meet him they found a large crowd of Chinese students already waiting to greet their guru. Unknown to the members of the Centre for Discovery and New Life, Penor Rinpoche was an extremely eminent lama with several established centres in Asia. Later they learned that back in Tibet he had been responsible for a hundred thousand monks and nuns situated in over a thousand monasteries. Like most of the great Tibetan lamas he had left his homeland in 1959 after the Chinese invasion. Starting with three hundred followers, he arrived in southern India fourteen months later with only 26: the rest had died on the perilous journey. Undeterred, he took the five acres of land and the elephant that the Indian government offered and, against what seemed insurmountable odds, proceeded to build a monastery that could hold five hundred. When Jetsunma and Wib met him his monastery was crammed to overflowing with 650 monks, many of whom had fled from the continuing persecution in Tibetn.

“Penor Rinpoche had a burning life.” Since he was young he had prayed to meet, in this lifetime, the reincarnation of Genyenma Ahkön Lhamo, the female Tibetan yogini who with her brother had founded his lineage, the Palyul sect, back in 1665. Penor Rinpoche was sure she was living on this earth somewhere. He had already met Ahkön Lhamo’s brother, a Tibetan who was also teaching in America in Ashland, Oregon. But he knew female reincarnates were immeasurably harder to track down. Tibetan yoginis, although reaching the same exalted peaks of consciousness as their male counterparts, were generally free spirits who did their meditations alone in caves. There was no system set up for finding them.

None of this was known to the small group of Americans who turned out to meet Penor Rinpoche’s plane on that spring day in 1985. What followed next was a scene befitting a Hollywood movie. Jetsunma described it to me in detail.

‘We arrived at the airport and there was this huge group of Chinese people who had got wind that he was coming and had arrived with a limousine. They knew who he was. We didn’t have a clue. They were all grouped around something or someone I couldn’t see, clicking their cameras and carrying on. Now Penor Rinpoche is short, about five foot three inches, and fat. I tower over him. I thought, “Well, I guess he’s in there somewhere, but what’s happening?” Somehow the sea of Chinese people parted, I saw him, and burst into tears!

‘Now I’m not the sort of person who usually does this kind of thing, you understand. I’m a hard-headed lady. I’m from Brooklyn, for heaven’s sake!’ she joked. ‘But I just could not pull myself together. I felt like such a ninny. I cried and cried, I just looked at him and thought, “That’s my heart…That’s my mind…That’s everything.” ‘ Her voice was soft. “How do you feel when you have just seen everything? I just knew that was it. That was what I’d been looking for my whole life. And the tears poured down my face.’

I asked her precisely what that meant.

‘Padmasambhava, the founder of Buddhism in Tibet, actually said, and I’ll paraphrase “I will reappear as your root teacher, the one with whom you have such a relationship that you understand the nature of your own mind. When you meet your teacher you will in some way see your own face, and it will be the face that turns around and moves you. It is the beginning of your awakening.” ‘

What is a “Good Death”

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

While there are individual experiences in the bardo of dying, let’s talk about the general ones so that we can prepare. Since we are talking about the six bardos, in general, we want to be very clear on the bardo of the moment of death, and that’s the last subject that we will cover today. It is a very, very important one, because we are all, in our way, preparing for death and we will all definitely experience death.

So, first of all, the bardo of the moment of death. We have talked about the point preceding death. Preceding death there is a period of time during which—and a person may or may not know—one has met with the conditions that will bring about the death. Now for those people who have a disease, a heart disease, or AIDS, or some disease that is degenerative or progressive in some way, the moment that the disease occurred to them was the moment that they entered into another bardo. Although it is still contained within the bardo of living, it is the bardo that preceeds death. What we’re talking about now is the actual bardo of the moment of death. That is when death is marked; it can be seen from the outside, and it actually occurs.

Before I begin I want to make something very clear. We have funny ideas about death. We have some terrible ideas about death. First of all, we’re scared to death of death. That’s the truth. I really didn’t mean to make a pun, it sort of happened that way. But we are scared of death, we are terrified of death, and it’s because we are unprepared. That’s the only reason to be afraid of death. And preparation, as it happens, will dispel the fears of death. I even think that during this week some of your fears of death may be dispelled, because you will be better prepared. But, in truth, until that time, we are terrified of death, and that is the main feeling we have about it. We do not understand death. We think that death is a horrible, sort of killing thing that we have to go through, and that the best way to go through it is unconscious. That’s the kind of idea we have. People often will actually pray, “Let me die in my sleep. Let me die unknowing that I’m going through the death experience.” And there are other people that say, “Let me die quickly.” Well, for my money, I would like to be one of the fortunate ones who know for some period of time before their death that they have caught the cause of their death or that they have the cause of their death. For my money, that’s what I wish would happen to me if I were an ordinary sentient being. If I were in that position where I was caught in samsara—and we all feel that way, we all are—I would wish to have preparation time. I would wish to know beforehand.

Those of us who are aging gradually and staying clear and in good health through the aging process, we are fortunate, because our minds are clear; and yet we can clearly see in the mirror that we are approaching this time. Clearly we are not the same person we were ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty years ago. Clearly that is true. We have pictures to prove it. These people are fortunate. We are fortunate. Because seeing the evidence of death approaching, we have time to prepare. Yes, we have to experience the discomfort of knowing that death is approaching, but it’s like going into the room, turning on the light, and seeing exactly where the stuff is so you can get around it. Remember we used that analogy early today, of walking through a room with all kinds of furniture. You want to do it when the light is on; you want to know how not to stumble. So this is what we are experiencing if we can prepare for our death.

Particularly, think about the tremendous suffering of diseases like AIDS. We talk about the tremendous suffering of something like that; and the biggest and most horrible part of it is that we die younger than we would have died if we did not have the disease. And that’s how we think about it. And yet, a disease like that gives us an opportunity. In a way, it is half of a blessing. In a way, it is the quintessential suffering of cyclic existence, couldn’t be worse. It is, in a nutshell, what cyclic existence actually is when you take away the barbiturate effect that it has on us. Yet, in another way, it is a way to understand —you understand clearly as never before—that death is imminent. There is a way to understand that you could not have had any other way, and it gives us extraordinary time. It gives us an extraordinary clarity of time to be able to practice because we’re motivated. It’s just that clear. We are motivated. We know we have a date to keep. Those of us who don’t know what that date is, we’re a little more vague about this. We don’t want to be bothered, frankly, and so we are at a disadvantage.

Less lucky is the stuff that most people pray for: a quick death. Instantaneous. “Hit me with a truck.” That kind of thing. That’s how people think, “Get it over with. Get me out of here.” And it’s because they don’t understand what death is. They do not understand that once the eyes are closed and the breath has stopped, it sounds like a pun, but basically life goes on in one form or another. One continues to continue. That is the nature of what we are. And so there is no true cessation other than the cessation of breath. To die a quick death may save a little bit of discomfort for the unprepared, but it gives us no time for preparation. Even the dissolution of the elements occurs in an untimely and hurried way so that we cannot cope with them well. So do not pray for an instant death.

Neither should you pray to die in your sleep, because it is too confusing. You are already in the sleeping bardo. The sleeping bardo has a heavier level of delusion in a way than the waking bardo, because you literally are not slowed down by the time it takes physicality to process itself. For instance, if I want to walk from here to that door it’s going to take me a certain amount of time and effort because of the physicality of the situation; but in the dream, I’m there, I’m out, I’m gone. I can go anywhere. So in a way there is even more delusion there. You do not want to die in the middle of the dream state unless your practice is so good that you would recognize the bardo even in the dream state; and that can only be hoped for if you are the kind of person who has complete control and direction over your dreams. Always. And that ain’t you. So instead, pray for a time of knowing and a time of preparation. Pray for the leisure to prepare for your death. That is the appropriate and best prayer.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

The Point: Pith Teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

The following is from a series of tweets by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo:

“Calling the Tsewei Lama from afar” does not mean asking for gifts and wishes fulfilled. It’s about devotion and faith. I mostly get requests for favors. Of course I will try to fulfill anyone’s wish. But Buddhists should also practice and learn so they can help themselves. That’s the point, as there may not always be a Lama to call on.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

His Holiness Khenpo Jigme Phuntsok on Dharma in the West

The following is an excerpt from a public talk given by His Holiness Jigme Phuntsok:

As we begin here this afternoon, I would like to mention a little bit about the great deeds of our sole guide and protector, Lord Buddha Shakyamuni, who before he became the Buddha initially gave rise to the awakened mind, the Bodhicitta, after which he worked for countless aeons to accumulate merit, finally culminating in his enlightenment under the Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya, India. Then 49 days later, for the benefit of all those gods and human beings and many others who would benefit indefinitely in future times as well, he turned the Wheel of the Dharma for the first time to bring the precious and holy Dharma into the world. Now, in fact, this is the auspicious day which commemorates the first turning of the Wheel of the Dharma, and because of that I feel that all of the outer, inner and secret omens have come together to make this a most auspicious occasion.

Also at this time, on this fully endowed occasion, in this world the greatest country that exists, the most sublime, the most exalted country in terms of fame and freedom and glory which is unequalled by any other, is the United States of America. Today for the first time I find myself in the capital city of this great land teaching the Dharma, and I am filled with joy. Furthermore there are three reasons why I am filled with joy. I feel that the leaders of this great land, who are actually the leaders of the world, are men and women who are concerned with bringing peace to this world and establishing the beings of this world in bliss and happiness. Towards this pursuit, they work effortlessly because they have the noble qualities and the abilities and the intelligence to actually make this come about. So I feel that they are here close to us, and this is the first reason why I feel a sense of joy: knowing that leaders such as this are in this vicinity.

The second reason I am filled with joy is because the general population of the human beings who live here in the United States of America are people who are endowed with a great amount of power and a great amount of material wealth. Just by the fact that they live in this country they also have freedom—freedom of choice and human rights. The condition is fully endowed. And when I think about all the people of this country having such auspicious and wondrous conditions, it is a great marvel to me, which makes me very glad.

Thirdly, the environment of this place, the particular endowment of the external environment, is that it is quite beautiful. There are beautiful rolling hills and forests, and although it is of cyclic existence, it seems to be somewhat like a celestial realm, a god’s realm, rather than an ordinary city. To see such a beautiful place as it is, I also feel great joy.

I had heard about this place before in Asia where I live, and it’s not until today that I actually come here. Now that I’ve really come and I am able to see for myself just how fully endowed it really is, that all the things that I heard are actually true and inconceivable, truly, then I feel even more joyful.

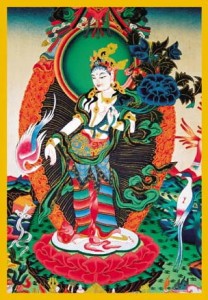

Now, we are Tibetan Buddhists, and in Tibet there are many traditions of Buddhism. Amongst them is the great Palyul tradition, the founder of which was the Vidyadhara Kunzang Sherab. Kunzang Sherab’s sister was the great dakini, Ahkön Lhamo, and she was very important in helping to establish and uphold the Palyul tradition at the time when it was first initiated in the land of Tibet. The great omniscient mind of primordial wisdom, His Holiness Penor Rinpoche, is the one who recognized her, who lives here in this land , in this incarnation, , I am especially happy to find her so well, in good health and so happy. To meet her here at this time gives me a great amount of joy.

As for all of the rest of you, the assembly of disciples, it is clear to me that you have very strong faith in the Buddhadharma, and this is also something that is very wonderful. You see, in Tibet there are many thousands of students who have been training in Dharma for many years, so it is not difficult for them to have faith and devotion, but here it is something quite extraordinary because this is not a Buddhist country. It is clear to me because of the kindness of Ahkön Lhamo who has brought many of you to the path of Dharma that this is why you have made this connection and this is why your faith is so strong at this time. I am very happy to see how this connection has been made and to see how the Dharma is flourishing here due to her kindness.

Especially too, here in the United States of America, with His Holiness the Dalai Lama as the leader, many other great lamas have come to this land, have stayed here for long periods of time and have given the Dharma teachings extensively. I visited some of those places at this time, however, the Dharma center of Ahkön Lhamo is different. I haven’t seen or felt any other place like it. That is because in Ahkön Lhamo’s center there are many ordained Sangha members. To see the robes of the ordained is something that brings me tremendous joy—to see how the Sangha, or the ordained community, has been established in the center. So, in particular, due to having seen the Sangha community flourishing in this way, I am extremely happy.

Generally speaking, in whatever country the Dharma may become established, it is very important for there to be a combination of the fully ordained, the partially ordained and the lay householders as a gathering of what we call the community of the Sangha. If you have just only the lay community and no fully or partially ordained community, it is incomplete, and vice versa. To have all of the different categories of holders of the Pratimoksha precepts together maintaining the Sangha community, it is considered to be fully endowed and complete, and that is what I see here in this center.

In particular, the category of ordination known as getsul, or novice, which of course includes the fully ordained, means those who have renounced the ordinary life of a lay person and who have taken on the life of an ordained practitioner. Now this status is something extremely important for the survival of Buddhism in any country at any time. This is something quite different from those who are called ngakpa, or mantra precept holders, who have no ordination according to the Pratimoksha per se. It is different because the doctrine can completely decline and vanish, and has over the course of time completely declined and vanished in places where there are only those holding the mantra precepts. In order for the survival of Buddhism to be assured anywhere in the world at any time so that it will always be flourishing, it is totally dependent upon the survival of the ordained Sangha.

Also as well in terms of the survival and the propagation of the Doctrine following this point of the survival of those who hold the Pratimoksha precepts, particularly that of full ordination, there is a prophecy from Lord Buddha which states that for 500 years occurring in ten successive stages of time, the Doctrine will increase and be propagated in the regions of the world. Now there are other prophecies that have to do with the land of Tibet and the Doctrine spreading to the north and surviving only in the north and then later going to the west and surviving in the western countries. According to this prophecy about the survival in the north, this refers to Tibet, which is the northern Snow Land of Tibet, the northern region of the world, and so there, of course, the lineage of ordination has propagated and survived. Then also according to the prophecy that it would spread into the west, that seems to indicate the western world, not necessarily western Asia. So when we look at the world in general and see now how in fact the lineages of ordination are moving into the western lands, then we can see how this prophecy is actually coming to pass. This is also something to rejoice about.

Henceforth, in general, because of Ahkön Lhamo’s efforts, the Doctrine is being established in this place, and also the lineage of ordination, which I will also pray, I do pray now and I will continue to pray to be ever increasing, to always be fully endowed, and that due to this there may always be peace and happiness for all the people of this place.

The Basis of Vajrayana

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Tools to Deepen Your Practice”

Today I would like to discuss the depth at which one practices. That is to say, how to avoid practicing in a superficial way where there is no mental or emotional investment. That’s really not the ideal kind of practice. It’s a little bit like watching TV, or listening to the radio, or something like that where you do it with half-a-mind, you know, and the rest of the time, of course, the mind is involved with other things. And so, we’ve all heard that we don’t want that to happen, that we want the mind to be gentled and stilled but yet we have a hard time understanding that really the key to that is the depth, the level, and the absorption with which we practice. That depth or that absorption is called the Dakini’s breath. That is actually what makes one’s practice relevant, delicious and sweet, meaningful and nourishing. Without that depth and that level of absorption, it’s very difficult to practice in any way that is more profound than say, recitation by rote. So that’s the effort that we want to make. In order to do that, I would like to explain things a little differently, perhaps a little more deeply than you may be used to.

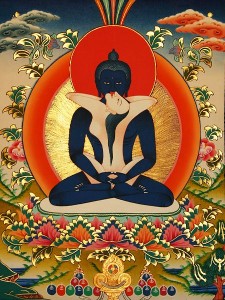

One of the things that I would like to mention is that in Tantrayana, or the path of Vajrayana (which is the same thing), which is where we are now, you could say that the Path has two eyes or two legs, two supports. Another way to say it would be that the Path can be distilled to its essential nature in two words: wisdom and compassion. In fact one sees in many of the thangkas, the traditional paintings that are all around, pictures of a female and male in union, two lamas as consorts in union. And of course having ordinary minds and being used to billboards and stuff like that, we think “Oh, what is this?” But we shouldn’t look at those pictures with an ordinary mind because they have a profound meaning. The meaning of the union between lama and consort is the union of wisdom and compassion, the union of emptiness and method. The union of emptiness and method is the perfect balance, the perfect ship by which to cross the ocean of suffering. It’s the perfect vehicle. And of course, first we should understand what it means. Wisdom and compassion or emptiness and method. . . What does it really mean?

Well the meaning is this. First of all, wisdom is something that you cannot arrive at by accumulating facts, because facts are phenomenal. They are believed to be self-existing. They are part of samsara, even if they are very smart facts. Even if they are PhD-style facts! Even if they’re MD-style! No matter how many facts you know, you can never accumulate wisdom through the accumulation of facts, or what we would call the accumulation of knowledge. It’s not to say that the accumulation of knowledge is not necessary. If that were the case, then none of us would need training. We would simply sit and do our best at meditating.

Of course facts are necessary. It is necessary for us in our practice to understand how it is that the preceding lamas and excellent practitioners accumulated merit and how they accumulated tremendous achievement. It’s tremendously helpful to know facts, for instance, about the great lamas and the great saints and the Buddhas that have come in this time, and in other times, in order to understand with our ordinary minds what it is about them, how they come to be. In fact, to some degree, our ordinary minds do require satisfaction. And that’s where Vajrayana is ideal, because Vajrayana gives us ‘mental food.’ We have visualization. We have mantra recitation. We have the absorption in emptiness and then the springing from emptiness as the deity; and then the vajra confidence and the vajra pride. It’s busy work! Sometimes when people who are used to just sitting quietly and doing whatever it is they do, you know, when they have that habit of just sitting quietly, and there is a part of Vajrayana Buddhism in which you do sitting meditation; but if students only have that experience, they come here and they say, “Well, my mind is not calm. I’m reciting all this stuff and I’m really stressed because I can hardly pronounce it. And the tunes—forget about it. And so there!” And of course the response to that is, “Well really in Vajrayana the task is not to calm the mind. The task is to awaken to the emptiness of all nature,to awaken to emptiness, that is, to perceive emptiness.”

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

A Great Opportunity

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered at Palyul Ling Retreat in New York 2012:

We have a great opportunity here. When I come here, I don’t take advantage because I am shy and I don’t like to come out, but I still practice and I still do what I can to benefit sentient beings. For instance, I think about ordinary things, and I think about how I can bring benefit to people who have ordinary lives and ordinary situations. One thing that I did was to start a food bank, so that we can feed the people in our neighborhood and in our community who have nothing. It is not a rich area. Those who have nothing can have food. They can come and get food for their families. There is no expense or anything like that. We do ask that if you take something, then bring something. If you take some beans and bread and that sort of thing, bring something, even if it is just a tiny something to make that exchange, to make that connection. There are a lot of people in my community that are eating very well because of our efforts. And I don’t feel like that is separate from Dharma. There’s practical Dharma and there is ultimate Dharma, and I feel that both are essential. And all are supported by the great bodhicitta.

Another thing that we have done is to create an animal sanctuary for rare and exotic parrots. Before these parrots came to us, they were abused. Many of them lived all their lives in cages that were too small for them to spread their wings. Many of them had never seen the sky. Many of them were fed graham crackers, and stupid things like that, that they should never eat. There was so much cruelty in the exotic bird community, so we decided to see if we could do anything. And we did. And now my son runs that exotic bird sanctuary, and all the birds get to go outside. We have a huge area for them, and they can actually fly, which they never could do before. It’s beautiful to see.

As you remember, His Holiness loved animals; he especially loved birds. In India he used to keep birds. When His Holiness saw the birds in the aviary, he was so happy about that. His Holiness saw them and loved them. He felt that that was Dharma in action. Activity Dharma.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved