An excerpt from the Mindfulness workshop given by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo in 1999

I’d like to talk about mindfulness in practice of making offerings. As you know, when you do your preliminary practice of Ngondro, at some point you accumulate 100,000 repetitions of mandala offerings. That’s a fairly elaborate practice where you sit down and you work with the mandala set and you make the mounds and you have a very extensive visualization. So is that where your offering practice stops? Do you make your offerings to the deities and then walk away from your practice and not be involved in your practice anymore? No, of course not.

In order to practice truly and more deeply, what we have to do is remain mindful of the practice constantly. Remember that we are trying to antidote ego clinging. We’re trying to antidote the belief in self-nature as being inherently real. We are trying to antidote the desire, the hope and the fear that results from that identification of self-nature as being inherently real and other as being separate. Remember that this is the point of what we’re doing. So if we were to practice accumulating mandala offerings, or make offerings at a temple and then have that practice end and no longer be a part of our lives, we wouldn’t be applying that antidote very well — at least not as well as we might.

How would it be possible for us to avoid this ego clinging? How would it be possible to avoid simply reinforcing samsara’s unfortunate message when we go around and simply enjoy ourselves? Remember that it is a worthy thing to notice, when you perceive something like a house or a tree or a flower, how automatic your reaction and response to that is. How is this flower going to affect me? This flower, this tree, how is it going to be meaningful if it doesn’t affect me? That is its meaning: it affects me. That is how we think. The practice that I’m suggesting is something that you can do without ever sitting down and meditating, so for those of you that have no time, this is a great practice.

When we’re doing anything, no matter what it is, we see appearances. Images come to us. They are sometimes very favorable, sometimes very beautiful, sometimes wonderful, and we enjoy them, and sometimes not. When we enjoy them, we enjoy them by clinging, by taking that experience, in a sense, and holding onto it, grabbing it. We’re grasping that experience. That tree is only relevant because I see it. Out of sight, out of mind. When the tree is out of my sight, it no longer exists. We think like that. My suggestion is that rather than just doing your practice when you’re sitting down, why not be mindful constantly? When you see the appearance of any phenomenon, when you see any kind of beautiful thing — like for instance when you look outside and you see how lovely it is out there, how gorgeous it is, the trees and the flowers and the sweetness of the air — how can you not let that beauty simply reinforce our clinging to ego, that clinging to identity?

One way to do that is to develop an automatic habit, and again, those habits start small and end up big. We start at the beginning, and we simply increase. Develop the habit of offering everything that you see. You think, “Huh? How can I offer it if it’s not mine?” Well, that’s not the point. Whether it’s yours or not, your senses will grab it as yours. You will react to it, you will respond to it, you will judge it, and so it becomes, in a way, your thing. You collect it. When you see something, you collect it, and you hold onto it. The experience is what you take away. Maybe we can’t take away the tree, but that doesn’t mean anything because we’ve taken away our experience of the tree. It has become ours, and it reinforces that delusion of self and other. Instead of doing that, isn’t it possible upon seeing something beautiful, upon taking a walk, having a good feeling, accomplishing something wonderful, seeing beautiful things, having meaningful relationships with other people, any kind of pleasure that is part of your life, that it can be offered? It can be thought of in a different way.

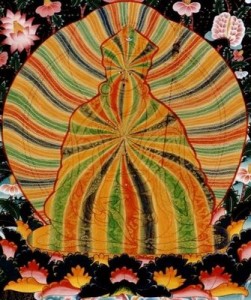

For instance, if I were to walk down the street and see a field of flowers, but didn’t know about any of these teachings of the Dharma, then maybe I might pick some of the flowers think that’s a meaningful experience because I feel good about it; I’m really happy with that. The only reason these flowers have become meaningful is because they’ve affected me in a certain way, and it continues the delusion. Having heard about Dharma, we have another option. When we see and enjoy a whole field of flowers, we can visualize in a very simple way, making it an offering to all the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Instead of that automatic clinging to this image and trying to take it with us, trying to make it part of us, there can be an instant habit that we form of offering this to all the Buddhas. “This field of flowers is so wonderful. I love it so much.”

If we work on it, instead of clinging to it in some subtle way, our automatic habit can be to offer it to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. Take any good taste, for instance, a good flavor in your mouth; a lot of times when we have a pleasurable experience like good food or good taste you may have noticed that ultimately it’s not so good. The food turns into…well, you know what it turns into, doo-doo. The experience does us no good because when we were tasting it, we were clinging to it. That’s mine. You see? I’m tasting it. It’s in my taste buds. It’s that relationship between my taste buds and that food that’s really important: we’re stuck in that delusion. We’re stuck in that dream.

Suppose we were able, instead, to develop the habit that when we eat something we are practicing as well by automatically offering the flavor and the taste of that to the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas? Then you’re not grabbing onto it, you’re not making it your experience. Offering it, you’re not reinforcing that dynamic of self and other, but rather when you taste, you’re just simply offering it. You can learn to do it very quickly. When you first start, it’s a little bit cumbersome because you take a bite of food, and you say, “Okay, I offer this to the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas.” You take another bite of food, saying, “I offer this to the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas.” At first, it may seem a little dry and uncomfortable, but there’s an inner posture that can be developed that’s an automatic response, as automatic as deciding whether or not you like that taste. As the taste hits you, the experience of that can be just offering it to the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas. It can be so immediate that no words are required. At that point, you’ve developed the habit of making this constant, constant, constant offering.

As parents, when we bond with our children and hold our children and have that wonderful, pleasurable experience of cuddling our kids and feeling wonderful, as ordinary human beings we think, “Oh, this is my child. This is the extension of my ego. I made that. I made an egg, and look what happened.” So we have very great pride about that, and our family becomes an extension of our ego, an extension of what we call ourselves. What if were able to offer that as well? As we hold our beloved children, as we feel that feeling, rather than putting another star in our own crown and thinking, “Oh, yeah, this is my kid and I’m holding her now” – what if we could offer that feeling? What if we could even offer the connection, the incredible, powerful connection between mother and child? That, too, can be offered to the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas. When you offer something to the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas, it’s not as though it disappears. It’s not as though the feeling disappears once you offer that feeling of loving your child to the Buddhas and the bodhisattvas, and suddenly you don’t love your kid anymore. It’s not like that. Anything that we offer, really in some magical way becomes multiplied. It becomes even more than it originally could have been. In not using what we see with our five senses as a way to practice more self-absorption, but instead using what we see with the five senses as a way to accomplish some kind of Recognition, this is a very powerful practice and a very excellent, excellent adornment for the sit-down practice that we do.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo