The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “The Guru Is Your Diamond”

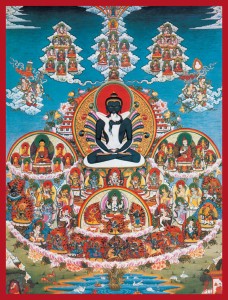

The original teachings of Lord Buddha taught us to take refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha, distinguishing between the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha and ordinary phenomena, samsaric phenomena. We use that idea of taking refuge in what is wholesome and what arises straight from the Buddha nature. We take refuge in this Buddha nature as represented by the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha and that starts us on a path of discrimination, where we can see what to accept and what to reject; what is wholesome; what arises from the mind of enlightenment as Dharma does, and therefore results in the fruit of enlightenment. In other words, the seed arises from enlightenment and the fruit is also then enlightenment.

So we are learning to discriminate by taking refuge. We see that we can take refuge in the Buddha and the Buddha’s Method, the Dharma, and the Buddha’s body, which is the Sangha, instead of what we used to take refuge in which was, who knows, sports or ice skating or, you know, watching TV or having three cars or twelve houses, or whatever people find their particular desire is in samsara. Now we’re beginning to understand that where we took refuge in things of desire, now we are taking refuge in something that doesn’t give immediate gratification in the way that getting a new car, say, would. Get a new car, you feel good for about six months. So good. If you get Dharma, maybe you would feel good for about six months, but then you start to feel better. And you begin to realize that you are creating the causes for continued happiness. And we begin that discrimination. Oh, the car wasn’t a cause for happiness. In fact, nothing I’ve ever bought or had has ever been a real cause for happiness. But the condition of my mind? Now that can be a cause for happiness, if I learn to accept some things and to reject others; and to live a more wholesome life; and to get a flavor of what it is to live in purity with uncompromised intentions.

Slowly, we begin to notice, ‘You know, I’m feeling better.’ Then we also begin to notice that it’s not all about me, that kind of self-absorption. Rather we are really taking refuge in the Buddha’s wisdom, the Buddha’s enlightenment, the Buddha’s compassionate and amazing intention. And it’s not all about me and what I want. And our mantra has changed from ‘Give me, give me, give me’ to maybe Om Mani Padme Hung or the Vajra Guru mantra, or even just the pure intention to practice Dharma. So little by little, we begin to move on the path.

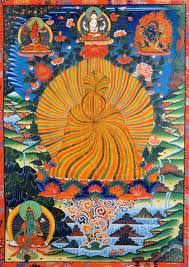

Now in this time and in this age, we have something quite special. This is the time of the ripening of the blessing of Guru Rinpoche. In fact, most of Guru Rinpoche’s teachings that were hidden as terma, or treasures, during the time of his life, have been revealed to come due or to be potent now. They are meant for this time that is very condensed and very degenerate, where people are really lost and our cultures even are lost, and our governments and power holders are lost. During this time when it’s hard to find even a rice-grained-size of truth, of clarity, and of compassion most of all, during this time, here it is that Guru Rinpoche’s precious teachings come ripe in the form of terma revealed.

In every cycle of terma revelation, bar none, Guru Rinpoche made it clear that most important was to practice Guru Yoga. Guru Yoga becomes to us the very sustenance on the Path.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved