An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Dakini Workshop

The Dakini is considered to be the enlightened or concerned activity of the Buddha nature. In order to understand the enlightened or concerned activity of the Buddha nature one should understand thoroughly the activity of samsara. In order to do that, one should observe one’s own activity. The key word to describe one’s own activity is effortfulness. Everything that we do requires effort. There is nothing that we can simply do spontaneously without effort. Everything requires effort; including starting with the effort it takes to get up in the morning and the effort that it takes to continue throughout the day. Every single item on our agenda requires some effortfulness.

Of course, there are degrees of effortfulness and there are degrees of ease. You can describe some things as being easy. You can describe some things that you do as being very, very difficult but the key word, the mark of samsaric experience, samsaric movement, is that everything one does requires effortfulness. That is the basis of it. And of course, in order to understand that basis of effortfulness, one must understand the foundation or the basis of activity. All activity experienced within samsaric existence is based on the idea of self-nature as being inherently real because the self is doing the activity. It has to be based on that. And in order for self to interact with the environment, self has to distinguish between self and other. That distinction has to be made. That is the activity that is going on in samsaric experience.

In order for that to happen, one must have attraction, repulsion or neutrality. One must interact with, or continue to meet up against and reinforce duality in every sense. Therefore, in samsaric experience concerning activity, there is always an inherent friction. Nothing slides through. There is no effortlessness. There is always a friction. There is always a bumping up against. That bumping up against has to do with the mind of duality and the distinction between subject and object. There is no movement in samsara without that. All movement occurs in that way.

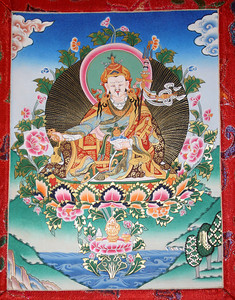

Therefore, in order to understand the nature of the Dakini and enlightened activity or compassionate activity, one must understand the concept of effortlessness. In order to understand the concept of effortlessness, one must understand the basis for the appearance of miraculous enlightened activity in the world, and that, which is consistent with the nature of the Dakini. The basis for enlightened compassionate activity is that this activity is consistent with, inseparable from and indistinguishable from, enlightenment itself – Buddha nature. That must be understood.

How is that distinct from ordinary activity? Ordinary activity has that friction and struggle associated with its basis. This basis is the fundamental idea of self-nature as being particularly solid. Remember that in order to determine self-nature, one has to distinguish between self and others, so immediately there has to be division, there has to be distinction, there has to be cleavage – there has to be a breakage of some kind. That movement is very hard. It is a movement very much involved in a solid process of continuing the continuum. That is the basis for any activity or movement seen in samsara. That is not the case pertaining to the nature of the Dakini, enlightened activity or compassionate activity.

If we can think of the nature of the Buddha we should think of the great sphere of truth, the undifferentiated expanse, the great sphere of emptiness. We should think that there is no basis for the sphere of truth, there is no basis for emptiness, and there is no building block or cause and effect relationship because there is no distinction within the great expanse. In order to understand the great expanse, the mind has to relax utterly. There is no arising of the components of distinction. There is no contrivance. There is no ripple or friction or cleavage or distinction of any kind. The great sphere of truth is simply suchness. The moment one tries to box up suchness or put it in a bottle or put in a certain shape or color it or distinguish it from suchness, it is no longer that. So, the great sphere of truth is as it is – simply suchness.

Yet, all potency arises from the sphere of truth. All that one sees, all richness, all diversity arises from the sphere of truth: that which we perceive as diversity arises from the sphere of truth. How can that be so? Either a thing is empty or it is not? Well, the mistake, the delusion comes after the idea of self-nature as being inherently real. At that point, the mind operates in the posture of distinction. It operates in the posture of duality. And everything that is perceived from that point is engaged in that process. Yet, from the point of view of enlightenment, when one has awakened to that nature and the view is correct, when one no longer engages in the process of distinction, when the mind is restful, spacious and luminous in the natural state, the mind is not operating in distinction. There is no distinction. And so, all that arises from the sphere of truth arises spontaneously and effortlessly and is spontaneously completed and insubstantial, like a rainbow.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved