The following is respectfully quoted from “The Way of the Bodhisattva” by Shantideva:

15.

Bodhichitta, the awakening mind,

In brief is said to have two aspects:

First, aspiring, bodhichitta in intention:

Then active bodhichitta, practical engagement.

16.

Wishing to depart and setting out upon the road,

This is how the difference is conceived.

The wise and learned thus should understand

This difference, which is ordered and progressive.

17.

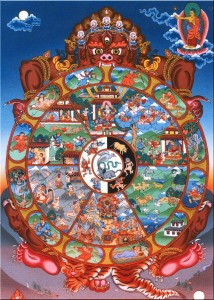

Bodhichitta in intention bears rich fruit

For those still wandering in samsāra.

And yet a ceaseless stream of merit does not flow from it;

For this will rise alone from active bodhichitta.

18.

For when, with irreversible intent,

The mind embraces bodhichitta,

Willing to set free the endless multitude of beings,

At that instant, from that moment on,

19.

A great unremitting stream,

A strength of wholesome merit,

Even during sleep and inattention,

Rises equal to the vastness of the sky.

20.

This the Tathāgata,

In the sūtra Subāhu requested,

Said with reasoned demonstration,

Teaching those inclined to lesser paths.

21.

If with kindly generosity

One merely has the wish to soothe

The aching heads of other beings,

Such merit knows no bounds.

22.

No need to speak, then, of the wish

To drive away the endless pain

Of each and every living being,

Bringing them unbounded virtues.

23.

Could our fathers or our mothers

Every have so generous a wish?

Do the very gods, the rishis, even Brahma

Harbor such benevolence as this?

24.

For in the past they never,

Even in their dreams, conceived

Such profit even for themselves.

How could they have such aims for others’ sake?

25.

For beings do not wish their own true good,

So how could they intend such good for others’ sake?

This state of mind so precious and so rare

Arises truly wondrous, never seen before.

26.

The pain-dispelling draft,

This cause of joy for those who wander through the world–

This precious attitude, this jewel of mind,

How shall it be gauged or quantified?

27.

For if the simple thought to be of help to others

Exceeds in worth the worship of the buddhas,

What need is there to speak of actual deeds

That bring about the weal and benefit of beings?

28.

For beings long to free themselves from misery,

But misery itself they follow and pursue,

They long for joy, but in their ignorance

Destroy it, as they would a hated enemy.

29.

But those who fill with bliss

All beings destitute of joy,

Who cut all pain and suffering away

From those weighed down with misery,

30.

Who drive away the darkness of ignorance–

What virtue could be matched with theirs?

What friend could be compared to them?

What merit is there similar to this?

31.

If they who do some good, in thanks

For favors once received, are praised,

Why need we speak of bodhisattvas–

Those who freely benefit the world?

32.

Those who, scornfully with condescension,

Give just once, a single meal to others–

Feeding them for only half a day–

Are honored by the world as virtuous,

33.

What need is there to speak of those

Who constantly bestow on boundless multitudes

The peerless joy of blissful buddhahood,

The ultimate fulfillment of their hopes?

34.

And those who harbor evil in their minds

Against such lords of generosity, the Buddha’s heirs,

Will stay in hell, the Mighty One has said,

For ages equal to the moments of their malice.

35.

By contrast, good and virtuous thoughts

Will yield abundant fruits in greater measure.

Even in adversity, the bodhisattvas

Never bring forth evil–only an increasing stream of goodness.

36.

To them in whom this precious sacred mind

Is born–to them I bow!

I go for refuge in that source of happiness

That brings its very enemies to perfect bliss.